Italy’s Radical Design movement rallied against both the political and design establishments; Its most fundamental output was discotheques. Opening across the country, and designed by architects including Superstudio, Gruppo 9999 and UFO, discos were considered a new space with potential for multidisciplinary experiments, creative and social liberation.

Art historian Germano Celant was the first to refer to the avant-garde movement as Radical Architecture, in 1966, responding to work that saw architects take on the design of objects and situations, atmosphere and multimedia artworks, as much as buildings or interior architecture. Many of the groups fundamental to the movement studied at the school of architecture at the University of Florence, with Umberto Eco. Interested in emerging mass media, he proposed a reading of the city and the architectural profession through the lens of communication, and challenged the notion of “function” as fundamental imperative. Speaking of the period in the preface to the catalogue, The Italian Metamorphosis, 1943-1968, which accompanied the exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim, Eco wrote: “Architecture departments became the arena in which everything was debated, because the architect felt responsible for society as a whole”.

[...] discos were considered a new space with potential for multidisciplinary experiments, creative and social liberation.

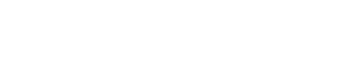

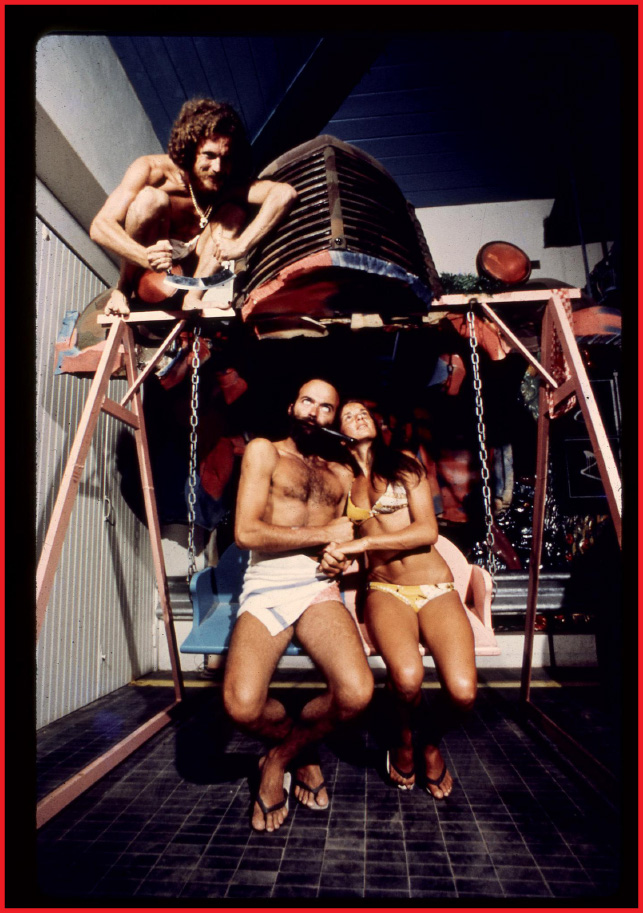

Architects of the movement were dissatisfied with the limitations of post-war design, and what they considered, “the crisis in modernism”; they sought to use their profession as a tool for change, in society and in their profession. Pipers was the first of the kind, designed by Manilo Cavalli, Francesco and Giancarlo Capolei; it featured reconfigurable furnishings, audio-visual technologies and a stage, with a backdrop of works by artists including Piero Manzoni and Andy Warhol. Space Electronic, designed by Gruppo 9999, was inspired by New York’s Electric Club and Marshall McLuhan’s media theory; Bamba Issa, designed by Gruppo UFO, was inspired by Disney comic book Donald Duck and The Magic Hourglass, “an allegory for capitalism, its arrogance and shortcomings”; and Ugo La Pietra’s Bang Bang was entered through a boutique, from which Perspex cylinders containing samples of the shop’s clothes would occasionally drop to the dancefloor through the night.

Although varied in style and form, these pioneering spaces were united in their innovative approach to art, music, theatre, technology, and architecture. They took utopian ideals and postmodern thinking and turned it into environments; multifunctional spaces for self and collective expression. Discos hadn't been explored as spaces with the potential for meaning and experimentation, the teenager had only recently been “invented”, and with a lack of expectation, discos propelled into spaces of wonder and amusement, while creating a new “aesthetico-political paradigm”.

As places with and for nocturnal lives, the discotheques and architects behind them could be otherwise occupied in standard waking hours – Space Electronic became an experimental architecture school, S-Space, by day. In 1971, Superstudio and Gruppo 9999 founded the Mondial Festival, with the first exhibition dedicated to “Life, Death and Miracles in Architecture”, for which they built a vegetable garden out of recycled materials on Space Electronic’s dancefloor. There was a dreamlike sense of cultural potential, an impression that architects, and society in general, could shift the socio-political scene via both critical engagement, and critical disengagement; collective joy and individual expression.

In practices that cross boundaries and challenge form shouldn’t be lost or undervalued. Utopian efforts may be doomed to fail, but efforts of collective imagination are only to be celebrated.